Ben Cooper, an undergraduate at Aston University, was on placement at BPHA during the autumn of 2025. He used archive materials to research how the death of Franco was reported in different publications. His article is printed below.

How the Communists reported the death of General Franco

On the 20th November 1975, General Franscisco Franco, dictator of Spain since 1939, died. He left behind a nation that had undergone nearly 40 years of fascist rule, technocratic reforms, catholic restorations, and deep unspoken political violence and imprisonment. This article explores how some communist movements reacted to the death of General Franco, using primary newspaper sources available at the BPHA (Birmingham People’s History Archive).

Who was General Franco?

General Francisco Franco was a Spanish military leader who ruled Spain as a dictator from 1939 until his death in 1975. He came to power after leading the Nationalist forces to victory against the Spanish Republic in the Spanish Civil War (1936-1939). Following his victory, Franco established a fascist dictatorship characterized by political repression, censorship, and suppression of opposition, especially targeting left-wing and communist groups. Despite some periods of relative stability during the 1960s and early 1970s, his regime was marked by authoritarian control and political crackdowns. His death in 1975 marked the beginnings of the transition to democracy under his heir Prince Juan Carlos I, as well as the formation of the Pact of Forgetting designed to prioritize the democratic transition.

Case 1: The Morning Star

The Morning Star is a left wing socialist/communist affiliated newspaper in England. Throughout Franco’s regime the newspaper reported extensively on its crimes against Spanish communists. Of particular interest is their front-page coverage of the dictator’s death on the 21st of November 1975.

The article has the headline ‘Spain Straining at its Fetters’, accompanied by an obituary of Franco written by Sam Russell of the Morning Star.

The obituary emphasizes throughout the democratic ideals for Spain in the wake of Franco’s passing. Russell quotes Spain’s communist party general, who said, “The long waiting period is over. A period in the history of Spain is ending. No to opposition forces […] must come out into the open to propose a provisional government and realistic programme capable of achieving national unity.’’ This highlights the sense of positivity that left wing forces found in the death of Franco, who for decades had persecuted

political opposition and eroded the democratic norms of the second republic. Therefore, we can see that the Morning Star decided to focus on the new found hope after Franco passed, rather than the legacy he left behind. Additionally, the paper features a political cartoon depicting Franco at what appears to be heaven, carrying a bag which reads ‘million murdered by Franco fascists’, alongside an outfit comprised of a hat akin to that of his Italian counterpart Benito Mussolini and what appears to be an SS uniform with a Swastika arm band. This bemusing portrayal simplifies his whole regime down to a cheap impersonation of the two other fascist leaders before him. Thus, the Morning Star reveals to us that the death of Franco to communists wasn’t just the death of a dictator but the death of an ideology and ideological victory.

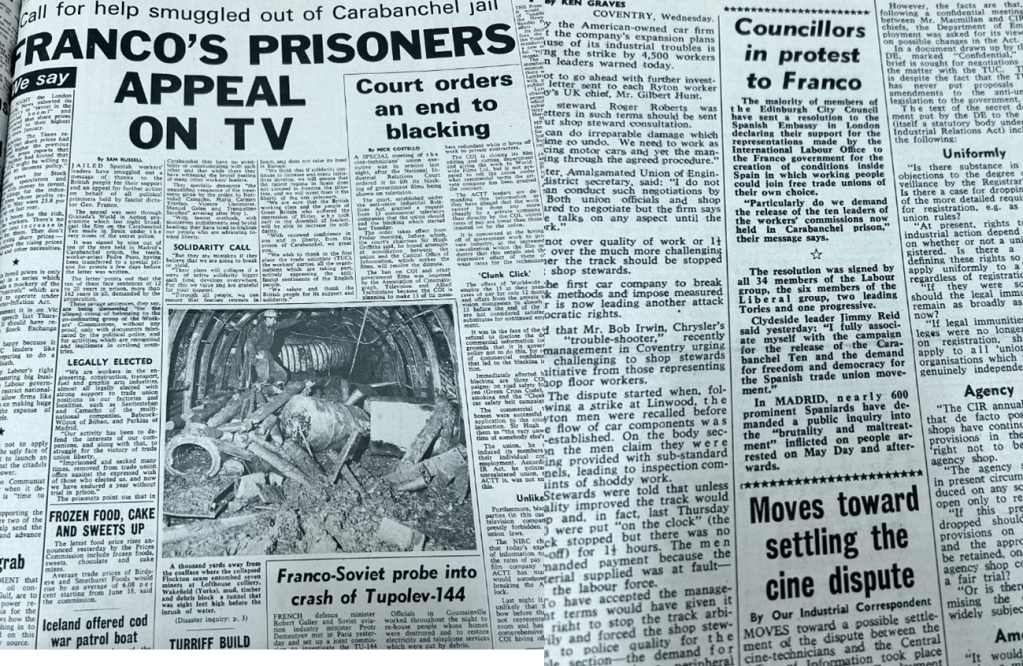

Additionally, the archive possesses earlier clippings from the Morning Star on Franco, as shown below:

These two clippings from June 1973 help gauge how the Morning Star was representing Franco whilst he was alive.

Case 2: The Soviet News

The archive also possesses archives of the Soviet News. These allow us to gauge how Soviets reacted to the death of Franco. While an article on the day after Franco’s death like the Morning Star one couldn’t be found, what the Soviet News published on the 18th and 25th of November allow us to piece together how the News framed Franco’s death.

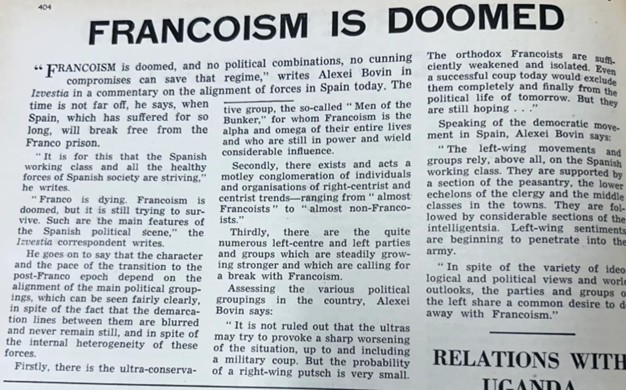

Here is a clipping from the 18th November 1975, from the Soviet News. The standout element is the bold headline ‘Francoism is Doomed’, which implies that the Soviet News saw the ageing dictator’s approaching death as a sign that not just himself, but his ideology and dictatorship, would die either with him or not long after him.

Throughout the article they explore the varying political groups within Spain that have vested interests in Franco’s death, from the ultra-conservatives who are reported to see Francoism as the ‘alpha and omega of their entire lives’, to the centre and right that are either nearly aligned with the ideology or not at all. Then to the left who are nowhere near aligned with Francoism. This article helps us see that communists, particularly the Spanish communist party, were hopeful that democracy would return to Spain before Franco’s death.

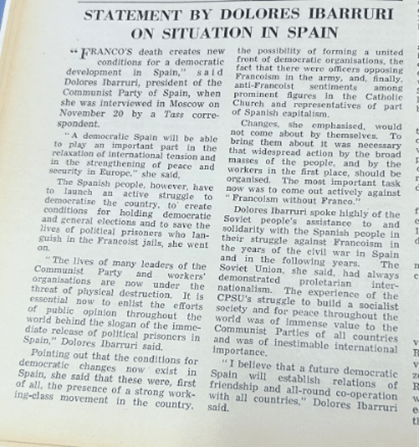

The Soviet News’ connections to the Spanish communist party are seen more clearly in this statement by Dolores Ibarruri on the 25th November 1975, five days after Franco’s death. Ibarrui was the president of the communist party of Spain. Therefore, her statement gives us valuable insight into how Spanish communists saw the death of Franco.

Ibarruri focuses on the ‘new conditions for a democratic development in Spain’, highlighting that to Spanish communists Franco’s death wasn’t about the death of the man himself, but his dictatorship, similar to that of the Morning Star. However, this primary document is more valuable to us as we can gauge how the actual Spanish communists reacted to the death of Franco, and more importantly how, to them, it was a sign that democracy can return to Spain after decades of dictatorship and suppression. Ibarruri highlights how dedicated the party would be to ensuring

Democracy in working with potential allies within the army, the Catholic Church, and even parts of Spanish capitalism to ensure a ‘united front of democratic organisations’ to dismantle the remnants of the old regime. Therefore, from the Soviet News we can learn that Spanish communists were more focused on the birth of democracy than lauding or celebrating the death of Franco.

Concluding

From these BPHA primary documents we can learn that to the communists, Franco’s death was less about mourning the dictator and military general and more about the prospects for Spain, particularly through the prioritization of democratic reforms and free elections – much more than the legacy of Francoism and the realities of it. The Morning Star and their satirical cartoon reduces Franco to a cheap impersonation of the two other fascist doctors, and Ibarruri’s statement relates to the future prospects of Spanish democracy and how it should be achieved. Overall, these documents are crucial in seeing how one of the most suppressed groups of Franco’s regime felt in the wake of his death 50 years ago.

Leave a comment