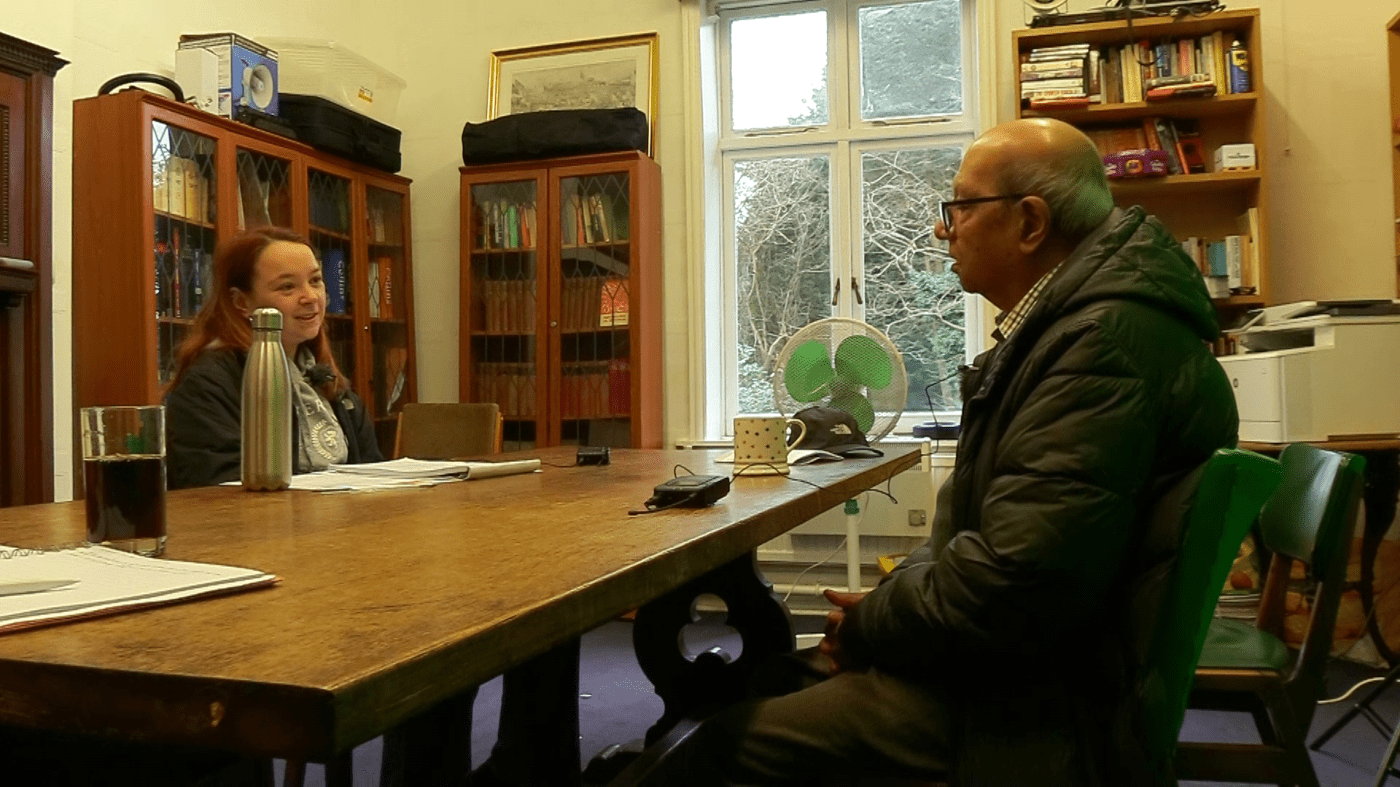

The following interview was conducted by Emily Potter on 27 January 2023, as part of the BPHA’s Historic England oral histories project. All photographs by Richard O’Neill, with thanks to Thomas Fattorini. Transcribed by Poppy Griffiths.

If you are a retired worker in the West Midlands who would like to tell your story, or if you know someone with a story to tell, get in touch with us at gill@bpha.online.

EP: So this interview is for the Birmingham People’s History Archive. It is the 27th of January. My name is Emily and I’m going to be interviewing Suryakant.

SS: Okay.

EP: Okay. So we’re going to start by just discussing your early life and your upbringing. So can you please tell me a little bit about where and when you were born?

SS: Originally, I was born in India and at the age of eight, I moved to Kenya because my father’s job was in Kenya. So from India, I moved to Kenya and for virtually up to 1970, I was in Kenya. I did all my school life there. Then from, after doing the SSC levels there, because there’s a different board of examinations there in Kenya. From there, I moved to India again to do further studies. So I was in there for, in India again until 1976. I did my B.Sc. in geology, physics and chemistry. So from there, in ’77, January, I came to the UK. And then the first job I had was in July, I think, in Birmingham. It was a jewelry company known as Birmingham Associated Chain Company, which is a group again. I was there till 1984. And in 1984, then I joined Thomas Fattorini Group.

EP: So did you move to England with your family or did they stay in India or Kenya?

SS: My parents originally went to Kenya from India, so they were there. My parents came here from Kenya directly. And I was in India first, doing the studies there. And then I joined my parents here. So my parents were here. My sisters are in India. So as far as the family is concerned, it’s just us now. My parents have passed away. So it’s just me and my family now here.

EP: And did your parents move to England to work as well?

SS: Yes. Because originally, you see, because Kenya was again a British colony, most of them had British passports, you see. So they had a chance to come here. So they did join. They came here in ’74, 1974.

EP: And what jobs did they do?

SS: Well, my dad was a fitter and laithe worker, a turning machine. And he used to work in a West Bromwich, you know, in a gun manufacturing company. I don’t know the name of the company. But he used to work in West Bromwich here.

EP: And how did you find the transition coming from India to England?

SS: I didn’t find it really much problem. I always had a thing in life that you just got to look at every step as it comes, as an enjoyment. And to me, it’s always been plain sailing. I haven’t had any problems in any sort of things. I mean, first of all, first three, four months, I had a problem getting a job here. Because when I first came here, I got a degree, you know, everywhere I went for a job interview they used to say ‘you are too overqualified for the jobs’. At that time, you know, they couldn’t see, understand that, probably presuming is because the payment wages, you know, because if you got a degree and all, they couldn’t give that much money and all. But eventually I got a job. And since then, I’ve just had basically in forty years, just two jobs, you know, one in jewelry company and the present one I had with the last one.

EP: So when you were studying for your degree, did you know what you wanted to do in the future?

SS: No, not really now, because basically when you say B.Sc. and all, there are general subjects, you know, so it’s how where you end up is really how you apply them, things is like chemistry, you know, like whatever I did now is applied chemistry, you see, because everything is to do with electroplating, where all the chemicals are used. So eventually that’s where it came in handy. So before that, you know, I had no inclination what sort of jobs I was going to do.

EP: So when you were applying for Fattorini’s in 1984, what was sort of the application process like?

SS: Fattorini’s when I first yeah, I did have an interview. I don’t know. I think there was a job application in the papers, a local paper, you know, the evening mail. So from that I did go into interview. And that was the time when I had the experience in plating because in the jewelry company, I used to do plating and also I had some experience about it, and so that’s how I got the job at Fattorini and Sons. And obviously, after two, three years, Thomas Fattorini took over the Fattorini and Sons, which automatically I moved on to that in Hockley.

EP: Do you remember the hardest question they asked you in your interview?

SS: The hardest question, it’s basically to do with how come, you know, because I was in jewelry trade before and then into this metalworking company, it was basically enameling and metal badges, car badges, things like that, because I had never done chrome plating before. So whether that would be any problem for me. And I said, no, it should be all right. You know, it’s plating, it’s plating. In that sense, I didn’t have much problem, but that was for me a step where I was going into unknown, you see. And because I had the background knowledge of chemistry, I could apply that there as well.

EP: And how come you left your original job in the jewelry manufacturer?

SS: Jewelry, at that time, I think there was a lot of problem with jewelry coming from abroad and all at that time. And the company went into insolvency and then I lost my job there.

EP: Is that a problem that you found a lot of people were having at that time?

SS: At that time, it was. Yeah, that was in 1984. Between ’82 and ’84, you know, there’s a lot of jewelry companies were having problems. So that’s why I think I was made redundant there. So I mean, for three or four months out of job. And then I got this Fattorini and Sons job and I was still the end of the retirement I was with them.

EP: So tell me about your relationships with your coworkers at Fattorini.

SS: Most of it is pleasant work. I mean, all the workers, it was like a family, actually, because there’s only about at most 60, 70 workers. And there was a lot of different departments. And I’d say right from the directors to the ground floor, the shop floor workers, everybody knew each other. It was like families. And it wasn’t any problem at such at all. We had a good time there. All the coworkers and management had a good relationship.

EP: That’s good. So tell me a little bit about the different departments that you could work with.

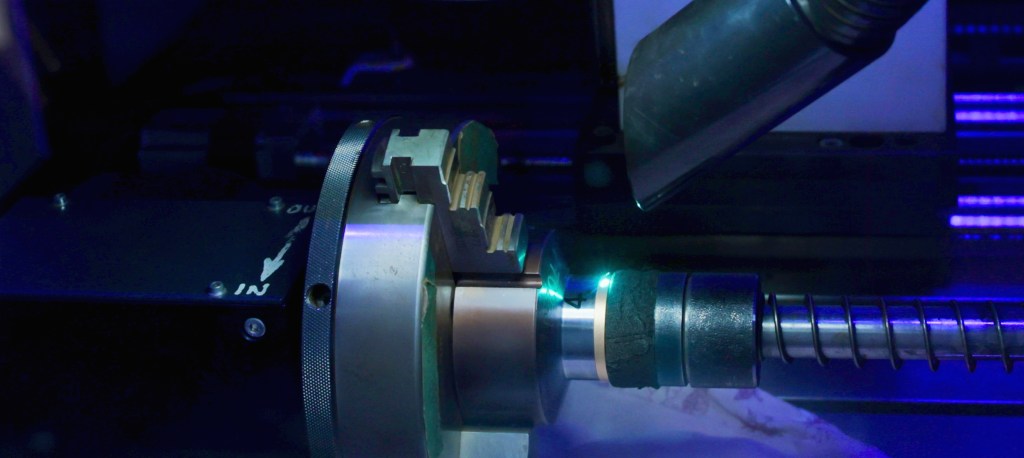

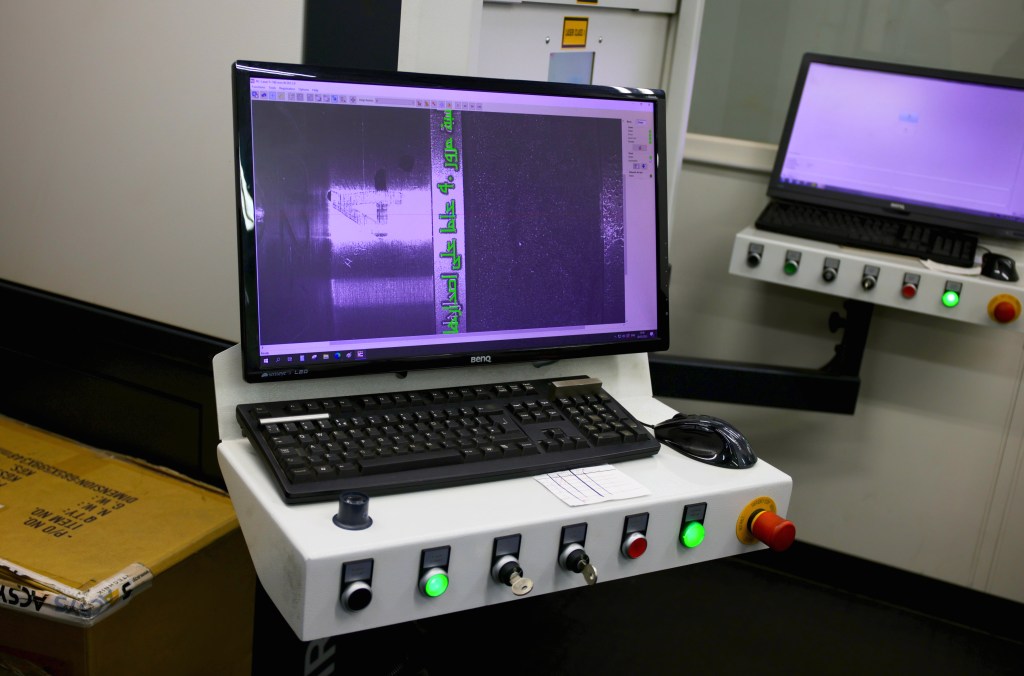

SS: Right. Ours was the finishing department, which is at the last. The first one is, you know, where the actual medals and all are designed as a design department. From there, it comes back to the press shop where the actual medals are made, a stamped and all. And then they come to our side, which is silversmiths. Silversmiths actually do the final work before it comes to the finishing. And finishing is where we do polishing, electroplating or oxidizing. That is, bronzing, silver oxidize and electro lacquering things like that. So basically, once it’s finished in our place, it goes to the production work where it’s certified and then checked and then sent away.

EP: So does it all happen in the same factory or is it?

SS: It is in the same factory.

EP: So can you describe how it would look for me in the factory?

SS: Well, when I say it’s the same factory, it isn’t the same factory, but the press work and all is done in a slightly different way, it’s across the road. From there, when it comes to our side, it is virtually enamelling and silversmithing, pumice polishing and everything is done here on our side. And when it comes to us, it’s virtually, as I said, before plating and all, it’s all polished, hand polished, checked all cleaned all. And then if it’s chrome plating, it goes through nickel plating or copper plating before it’s chrome plating. And the gold and silver are directly on gold and silver. So either it’s 22 carat gold or it’s 18 carat gold, you know, it depends on what people are asked for.

EP: So what kind of clients did you have? So what sort of things were you working on and who for?

SS: Basically, you know, in the car manufacturing, we mostly worked for Bentley’s, Rolls Royce and Aston Martin badges. And the other end was the school badges. Right from prefect badges, monitor badges, head girls, head boys, everything in that sense. And there used to be a head boy and head girl used to be in silver as well, which were enameled first. They were pressed and enameled and then come to us for polishing and plating things like that. So virtually everything that people wanted, I mean, jewelry trade as well, is to do cufflinks, different trade in horse racing companies, cufflinks. And different car manufacturers had special cufflinks of theirs like a Bentley badge, a small B. It was engraved on it and also things like that.

EP: Did you have a favorite thing to work on?

SS: The favorite things were I mean, some of the things we used to do is middle eastern countries. There used to be oxidized silver jobs and antique gold finishes, which, you know, the middle eastern countries really preferred that. And all their armed forces badges were done, armed forces medals and the trophies and all we used to do. So that sort of finishing touch, which needed really good experience and how to do them and all that, that was the best thing to do.

EP: When you first started working there, did you find the transition difficult? Did you find it hard to adjust?

SS: At Fattorini?

EP: Yes.

SS: No, I mean, I was working for Fattorini and Sons before joining Thomas Fattorini. And it was like once they took over in Fattorini and Sons, it was just like a family around there. I mean, Tom Senior, he was the director. He used to come once a week to meet everybody there. And since then, we actually had no problem. It was really a good company to work for.

EP: So it didn’t change much after it moved from Fattorini and Sons to just Thomas Fattorini?

SS: It wasn’t a big issue at all. It was really smooth sailing all the way.

EP: And were you aware of… The close relationship you had with your co-workers and your superiors, Do you think this is something that was quite unique to your company? If you’ve spoken with people who maybe worked in different factories?

SS: I think it basically depends on individuals and how they approach different jobs or how they approach their colleagues and all that. Because sometimes, all right, there’s a tension, but if there’s a tension or there’s an argument or disagreements, then you go settle down there and not take it personally. If you take it personally, then obviously you get a problem and you don’t get on with people. I think if you just leave it, let it go, then it’s okay. Then we stay with it for a couple of hours and then we will be friends again.

EP: Was there a strong social element? So did you do things with your co-workers outside of the job?

SS: We used to go out socially. I used to maybe every once or twice a week. I used to go in the evening to the pubs and all. So it was social gathering, and Saturday, sometimes used to work over, so Saturday afternoon, we used to go up as a group to the pub.

EP: What were the hours like?

SS: Hours were from eight to five. And obviously, there was overtime if you wanted to do. I mean, in my life, there was never a time that we couldn’t do overtime. There was always work there. So it was quite a stable and good company to work for. If you needed money, then there was more work there.

EP: And were the wages sufficient for your cost of living?

SS: Yeah, I think compare it to now, we were quite happy with whatever we were getting yeah. I think we didn’t have any unions as such, you know. So there was no argument as to how much we were getting. If it’s less or more, we never used to know, you know, because if you got unions, then they’re saying these people, the other companies are paying more wages than that. But so we didn’t have that issue, you see.

…we didn’t have any unions as such, you know. So there was no argument as to how much we were getting. If it’s less or more, we never used to know, you know, because if you got unions, then they’re saying these people, the other companies are paying more wages than that. But so we didn’t have that issue, you see.

EP: Is there a reason that you weren’t involved in the unions or the factory wasn’t?

SS: I’ve got no idea. I don’t know if the company never had a union. So whether it was a policy that they used at work, I don’t know.

EP: Did you have an opinion on it at the time?

SS: No, no, no opinion on it. I mean, I think, you know, personally, as you go into a company which is working healthily and seems to be happy with everything, you know, that there was no issue with anybody. I mean, you know, as I said before, that sometimes you get disagreements but, you know, as long as you can settle it within yourself, then you don’t need people from outside to settle it for you.

EP: What sort of disagreements would there maybe be?

SS: Well, normally it’s sometimes you find like in a work situation, like our department was the last turn. So if there was any fault somewhere, you know, and it was blamed on us, oh it’s finishing department you know. Because if the work comes from us, from a silversmith or enameling shop or something like that, if their work is not up to standard, then, you know, we can’t produce good quality from that. But because it’s ours is the last one, they think, oh, it’s our fault, you know. So they used to be the issues like that. And we could sit around and solve them. So if it’s enameling shops problem, then they should make sure that everything is perfect before sending it to us. But again, in between is a production department, which actually handles, it’s a heart of the company, which handles work from all the departments. So it comes to them and they check the work before forwarding to the other departments. So obviously it’s their job to make sure that everything is running smoothly.

EP: So as the finishing department, did you feel pressure that it had to be perfected?

SS: Pressure in such a way that, you know, because timing is essential as well, because if the order is, for example, the order comes in at first of a month and the time is delivered, it’s in the 30th of a month. What happens is by the time we get it, it’s about 25th or 26th, you know. So all of a sudden, I will start looking for that order. And then it’s come to us at the last minute, you know, which is then you can lose quality in that time, because if you haven’t got enough time, the quality suffers. So they always make sure at least one week before it’s going out, you know, we have it.

EP: And how long would the process of finishing normally take?

SS: Well, it depends on the job, you see. Sometimes, I mean, sometimes you get 1,000 badges, you know, on an order. Sometimes you get 10 badges or medals. It’s some type of job that is actually coming to us. If it’s badges, you know, normally we get three hours to do about, probably one hour to do 100 badges, you know. So virtually if it’s thousand, you get 10 hours, you know. So in that sense, you have to just adjust it accordingly, you know, how to time it and do it properly.

EP: And was it hard work?

SS: It was hard, you know, but enjoyable, yes. I mean, always, sometimes it’s stressful, but we always managed to do it, yeah. Because we had about five or six of us in the finishing department. And we used to share the work, you see. Some people used to polish the work. Some people used to plate, electroplating work. So, you know, in that sense, you know, I used to share it along. So, you know, everything went smoothly then.

EP: So were you quite close with the people, especially in your department?

SS: Yes, we were. I mean, if you look at it as a deeply, you know, there is always a disagreement in some places. But as far as work was concerned, now we still always have a good relationship.

EP: So can you describe a sort of regular day and how it would look like?

SS: Regular day. I mean, I’d say everybody mostly the work used to start at eight o’clock. But most of us used to come there at half seven in the morning. So we used to have a cup of tea or coffee, chat amongst ourselves, go for a walk. And then by the time the work started, we were all ready to go. And each one, the prior days were previous days where we knew exactly what we were supposed to do. So we used to take them orders and start looking into what needs to be done. And accordingly, we used to start the jobs at eight o’clock. And mainly, you know, let’s say if individual one job says it’s about 100 badges, it takes about a couple of hours to polish them and clean them and all. So the person who is doing this, so it takes a couple of hours to clean them, polish them, clean them and then set ready for plating. So this way, within one day, you can have two or three different jobs. Or if it’s a big order, like 2,000, 3,000 badges, that job, one person can go up to two or three days. So that’s how it was done.

EP: Did you enjoy more doing the different things in a day or did you like dedicating yourself to one project?

SS: I think I preferred doing different things, you know, because sometimes, as I say, if you’ve got 10,000, 20,000 badges, you’re stuck on one job for more than a work two or three weeks. It is enjoyable, but again, you know, you get bored with doing the same thing again and again. So what happens is if you’ve got small jobs, you know, you can go three, four orders in a day or in a week, you can do. Some medals, you know, you have to be with medal work, it’s quite extra work, you know, you’ve got to be more careful, more details on it. So you have to look at the production and how to do it properly and all. So sometimes it’s just like much more time to do even a small quantity at a better finish, you see.

EP: And what were your lunch breaks like?

SS: To start with, we had one hour lunch break, 12.30 to 1.30. But then last, 10, 15 years, it was 45 minutes because we were then, from Friday, we could leave early, you see. So a quarter of an hour, we still live a quarter of an hour every day. So on Friday, we still have about two hours, so we used to live at 1.40 instead of four o’clock.

EP: Which way did you prefer?

SS: I didn’t have any problem, you know, I say. I say if you leave early on Friday, it was a good day because then you go home early and have some relaxation time with the family.

EP: How did you find balancing your work life with your family life?

SS: It was difficult when our children were young, you know, because it was really, first I think, up to the time they were old enough to go into higher senior schools, I didn’t have much relationship because I used to get up about half past six in the morning. I used to come back half past six in the evening, so I didn’t have much time spent with the children. And it was only Saturday, even Saturday afternoon, up to 12 o’clock I used to work, so virtually hardly any time for kids. And that sort of things, I regret doing it because I was working so much that I missed some of the growing up of our children. My wife used to look after them because she used to work, but then she had to actually look after the children more than my share of the work, you see.

EP: What did your wife do?

SS: She was a home care assistant, and she used to work morning from eight till twelve and then in the evenings six till ten. So when I used to come in the evening, then she used to go out, you know. So during the school works it was alright, but when the children’s holidays, they had to find the child minders and things like that, so it was difficult in them days, yeah.

EP: Was that difficult finding a child minder?

SS: At that time it was pretty good, but again, that’s another expense going out, so it was difficult in them days, yeah.

EP: So were your wages mostly spent on the family and your children, would you say?

SS: Yes, yeah. Because we were both working, so that’s why we could afford to buy a house later on, because my wife’s wages, you know, we used to save it all the way, most of them we used to save it to accumulate a deposit for a house, and that’s where we could move forward.

EP: Did you ever spend your wages on holidays or things like that?

SS: We do, we used to go quite a lot, I mean, we spent mostly, we used to go towards South Devon and Cornwall, then we travelled Lake District, most of the places in England and Scotland, and we went abroad a couple of times, we took our daughters to India as well, and we went to Egypt, we took the daughters there, and some of the European countries, Spain, so yeah, but whenever we could afford it, we could still move, we used to go, and even eating outside, it was difficult sometimes, but you know, we used to take children out, eat restaurants, you know, so quite good fun.

EP: Did you miss India being in England?

SS: To begin with, yeah, when we first arrived, you know, it was totally different environment, you know, I mean, in India, you know, your life, you know, especially the weather wise, it was vastly different, you know, because it’s always sunny there, you know, so, and so that side I missed, you know, to start with. But once we settled down here, and we went back to India, you know, we couldn’t handle it because it was too hot for us as well, you know, then, so, you know, that climatically, as soon as you move to a different place, you know, it seems to adjust to one area, and then suddenly you go back to that, you don’t like it.

EP: Did you find a strong community moving to Birmingham?

SS: You see, I mean, in India, we are from Bombay side, you know, and there’s not a lot of community from our side here in India, in England, you know, mostly they’re from North India or South India. And so we didn’t have as a community our people here, but there is Indian peoples here, but mostly, you know, in our time, you know, we mostly there is to meet in temples, you know, to have a social gathering, you know, like Diwali festivals and all festivals, which may be meeting temples. And that’s how we communicate during that time. But socially, we used to have friends, you know, every week, weekly, once a week, you know, Saturday or Sunday, we used to meet and go to each of those houses and have communication.

EP: So you were able to maintain quite a strong sense of your Indian identity when you moved here, would you say?

SS: Yes, yes, yeah. I mean, Indian and English people wish to communicate. So it’s a very good relationship with our neighbours and people like that. So we used to go out drinking and pubs and also a good place here.

EP: Did you ever suffer discrimination based on being from a different country?

SS: No, I mean, I personally haven’t suffered, you know, because I say I’ve always I think I do feel still feel that it’s up to individuals and how they handle the situations. If you and if you don’t can’t handle it, then, you know, it’s difficult, you know, because I mean, you always get wild comments from people, you know, and, you know, you get just go to listen to it and just let it go. If you if you keep it in your mind, then I think it makes you more hurt. It hurts you more than it should, you know, and touch wood I was OK. You know, I didn’t I didn’t find that much too much.

EP: And in your factory, were there a lot of immigrant workers, would you say or was it mostly local Birmingham workers?

SS: Mostly, I mean they were all around from Birmingham and close. I mean, people, one of my friends comes from a Stourbridge. And Wolverhampton, there’s a lot of people come from Wolverhampton as well. So they’re coming close from the West Midlands.

EP: So you worked obviously at Fattorini’s for a long, long time. So from 1984 to 2019. So what are the biggest changes that you noticed whilst you in your time working there?

SS: From the time when I was first came in 1984. Gradually, I would say first few years, as far as the relations were concerned with the co-workers and all because I came from Fattorini and Sons into Thomas Fattorini, they were already well settled and I was new. And for the first few months and a bit of a difficult time adjusting to their way of working, I say that. I mean, everybody’s way of where working is different, you see. So at that time, I had a bit of time adjusting to their way of working. But when I came to Thomas Fattorini, I must say that they were working with much better than what I had at Fattorini and Sons and that more modern equipment and technology there. So I did get adjusted to that. And then once I got adjusted to that, I was pretty good. And it was OK. Yeah.

EP: So would you say the technology was one of the biggest changes throughout your time working there?

SS: Modern technology was. Yeah, because there were plating equipment, the amount of different qualities of equipment was much better than what I had there before. So in that sense, it was very good. Yeah.

EP: And is that something that continually developed while you’re working?

SS: Yes. Yes. Yeah. I mean, I would say in the last 10, 15 years, we had a new works manager was Gary Speakman. Once he came in, he was also coming from Johnson Matthey, you know, which was near us. And he brought with him the new technologies of finishing. And as at that time, you know, different chemicals were not supposed to be used because of harmful to environment and all. Some chemicals weren’t used and that was phasing out like triploethylene. You know, we used to use it for drying components, which was phasing out. And we had difficult to find replacement for it. And he was Gary Speakman, he had better knowledge of different places where he could get better equipment and different chemicals to start using them instead of triploethylene. So in that sense, yeah, as it was progressing, you know, we had better finishing and materials.

EP: Did it make the job more enjoyable, having that sort of ease of technology?

SS: Yeah, it did. Because, as I say, it makes your life much easier because sometimes if you’re doing things that are old ways, you know, it’s difficult to I mean, old are much better anyway because you get good finishes but it just takes a lot of time. With a new technology it’s better to get into the situation where it cuts down the time and get a better finish as well. So everybody’s happy.

EP: So can you tell me a little bit about the social history of the time?

SS: To start with, you know, I came to this country in 1977 and that time the infrastructure and I said the local buildings, if you look at in jewellery quarter, it was heavily industrialized. You know, I mean, there was so many companies like us and there used to be canning, laboratories and everything just next to each other and it was heavily industrialized. But as gradually things started getting to eighties, nineties, most of the companies, for some reason, I think because of the decline in manufacturing of medals and all some companies lost their footing in the jewellery quarter. Some moved out of Birmingham and slowly started becoming a more residential area.

And if you look at it now, most of jewellery quarter is ,70 or 50 percent of the jewellery quarter is, really residential area. Now, there are only a few manufacturing companies are still there. And most of that is actually small jewellery companies. The big industry companies are just gone. So, I mean, so all of heart of Birmingham, I mean, say from Barr Street towards city centre, all that was there was all medal making and badge making companies and different. I mean, there was a Lucas big company of Lucas used to have been in Hockley and that’s that disappeared long time ago. So things have gone from jewellery manufacturing to more of a residential area now in Birmingham. And I mean, building some of the buildings I never recognize it, you know. But 20, 30 years ago, and what they are about now, what they are now is totally different.

EP: Can you think of any reasons why maybe the jewellery industry started declining in the 80s and 90s?

SS: Well, the main reason was imports of cheap jewellery from outside, mainly from just coming from China, the far east, you know, country as China, but mostly from far east. Some of the thing is coming from India. So things like and so obviously, you know, manufacturing here is getting more expensive. So I think people couldn’t afford to do it here. So that’s why some of the companies started closing down.

EP: And did Fattorini have any sort of unique policies that allowed them to stay on their feet?

SS: Fattorini, even in the last 10, 15 years, they also imported quite a lot of work from China. I mean, basically, it was the school badges, you know, because manufacturing of school badges was getting more expensive here. So they used to import school badges from China. You see, the enamelling process itself is it’s very labour enduring. And so some of the Chinese, you know, they seem to produce the goods that half and more than less than half the price is. So obviously, most of the companies still do import from China and then distribute it here.

EP: And did importing change the way you worked?

SS: Not directly. Didn’t involve me because what we used to get from China was really we could do away with you know, because it was more time consuming and less productive and less profitable. You see, what we were doing was specifically specially trophies, medals, finishes that we’re doing, you know, that they couldn’t do it from China or anything. And so oxidizing antique gold, antique silver, bronze medallions, you know, these sort of things, you know, it’s difficult to get a good quality from China. So these sort of things, we kept it at a high quality so people could buy it at more expensive. They were willing to pay higher prices for them.

EP: So Fattorini, the ethos of the company is make it once and make it well. Did you feel like this was very much reflected in the style of work you were encouraged to do?

SS: Yes. They heavily rely on good quality work and produced excellent work so that people can willingly pay for it, especially the Middle Eastern countries, you know, like Emirates, all the Emirates and all the good military medal medallions and things like that. Even the Emirates airlines, you know, we used to make badges for them, which is a high quality work, you know, and they’re willing to pay for it. So we maintained that high quality to get good work from them.

EP: So did you feel proud in your work?

SS: Yes, obviously. Yeah, we’re all proud of what we produce, you know, because at the end of the day, our quality of work was the companies outlook, you know, so we have to make sure that we produced good quality work for people to admire.

EP: And were you proud of the like belonging to the company as a whole.

SS: Yes. Yeah.

EP: Were you very much aware of sort of the prestige of Fattorini given its history?

SS: Yes, I mean, right from the word go once we move into Thomas Fattorini, you know, and the quality of work they were producing, I actually got more involved with it and I learned more there than I had before. So the quality of the quality of the work and new machinery is the hat, you know, all this. There are different sand blasting processes, you know, which are needed for this sort of work. And it was quite joyful to work there.

EP: So can you remember any sort of key political historical moments that happened while you’re working at Fattorini’s?

SS: The key political, I mean, when Prince Charles was a prince, he visited our company. I think it has to do with what he does. You know, he gives the work to different communities and all he shares his. I don’t know. But some of the employees, the two, three employees which were there from his. I would call it. I don’t know. But they were company from youngsters, you know, 18 years old and all that they came there from his trust. That was the word. His trust, you know, he was financing them and he came in once to look at how they were progressing and what sort of work they were doing. So, yeah, we had a big moment there when he was a prince, you know, he came to our company.

EP: Was that one of your most memorable days?

SS: Yes. Yeah. It was good to see there are people coming to the company.

EP: Any sort of broader political moments that went on that might have impacted the way you worked or the way you lived in Birmingham?

SS: I mean, mostly, I say, Middle Eastern visitors, you know, they used to come in first to see the company, how what sort of products we do, how we finish the work and what sort of our products, products are. So we had mostly stuff from Middle Eastern countries, you know, as far as the political view is concerned.

EP: And how about the gendered relations in the factory? Was it mostly male or were there women who worked there as well?

SS: No, I think mostly it was maybe 56, 50, 50 or 40, 60. I mean, I say enameling shop is where mostly it’s craft work, where mostly the female work was in. And in the finishing job, we had a couple of girls, you know, doing what they used to, because some of the work is craft work, like, you know, they were quicker at doing the work. So there were girls and all that. There wasn’t just one gender as mixed.

EP: And what were the relations like between the genders in the factory?

SS: It’s quite good, actually. There wasn’t any problems as working with different males or females. It was quite good. Yeah.

EP: that’s good. And was there a high population of immigrant workers?

SS: No, I think it was about six to seven from different backgrounds. I mean, it wasn’t as if we had any issues. It was quite a good relationship. As I say there’s always some sort of problems, but if you don’t take it seriously, then it’s all right. You know, it doesn’t seem to affect you.

EP: Did your co-workers have the same attitude as you?

SS: Yeah. Yeah. Yeah.

EP: That’s good. So what was your favorite part of the job, do you think, over your 30 years that you worked there?

SS: I mean, to be honest, how the day progresses, you know, how you. Basically when you’re working there, you know, as long as you get on with people around you, immediately in your area, working area and all. I think if you got a good relationship with people, you know, then your life goes much, much easier, and the time goes quickly as well. But that’s how I felt. You know, I’ve always had a good relationship with mostly everybody. So I didn’t have any issues. You know, the days used to go really quick. I really enjoy the work here.

EP: That’s good. And did most workers stay for as long as you did?

SS: Yeah, I mean, so there’s mostly from my age, you know, my age group. I didn’t see anybody going before retiring. They all retired and went. So in that sense, yeah, the younger age groups, you know, which were recently coming in, they probably didn’t last that long. You know, because they had different agendas, different jobs at the time. But when I first moved in ’84, where were they? They were still there. Some of them haven’t retired. They’re still there. Some of them retired before me. Some of them retired maybe after me. So, yeah, the whole batch of people that were working with me, they’re still there. Yeah, I didn’t think I see anybody leaving much.

EP: And do you think if you know people who work at other companies, do you think that’s a unique concept of Fattorini’s? Or do you think in your generation, it’s quite common to stick in the job that you have?

SS: Well, I mean, these days, not many people stick with my job, you know, but in them days, I think people did because it’s mostly to do with security. I mean, that time, you know, nowadays, I don’t know how people approach work, you know, but in our time, you know, we used to have like job security, you know, a good mortgage, you know, so I pay for the house and the general running of the house and running of the family and all everything. So, you know, we always used to respect the job. And that’s how we always looked at the job. It wasn’t just a job, it was like an aspiration to do, you know, work properly and stay in the job, which present day, generation is a totally different approach to work. So in that sense, yeah, it was quite a good thing.

EP: And did the company have policies which guaranteed you job security?

SS: Well, yeah, I would say I haven’t seen anybody actually sacked for unnecessary, you know, unless you really had some bad issues with the company and then it was otherwise, you know, basically everything was alright. And they also had a private pension policy and which company provided it, you know, we didn’t have to fund it or anything. So in that sense, it’s very good as well.

EP: So what were the other benefits to the job beyond economic benefits?

SS: Well, benefits in the other sense is like having social life, you know, it’s virtual, I say it’s like a family business, you know, so you’re spending most of your time there, you know, virtually, or eight hours, nine hours a day, you know, so to get on with people and enjoy life. It can be the best way to spend your life, you know, otherwise, you know, if you don’t get on with people, then it’s virtually even an hour seems like a day, you know. So in that sense, it was quite good. Yeah.

EP: Yeah. Do you have anything about the job that you want to bring up something that you feel passionate about that you want to discuss?

SS: Not really. I mean, I say everything that I did, I really enjoyed it. So I had no problems. And so everything was fine. Yeah. I mean, all I can say is I really enjoyed the company. You know, it is a family company. There’s always things to do there so it was quite good.

EP: Okay, nice. Should we wrap it up there?

SS: Yeah

EP: Sure.

Leave a comment