Birmingham People’s History Archive are proud to hold the personal papers and photographs of Albert Knight 1903-1979), trade unionist and alumni of the Central Labour College. Here, one of our newest volunteers, Toby, presents the fruits of his research on this important strand of British labour history.

What was the Central Labour College?

The Central Labour College (CLC) was a higher education institution funded by and provided for by various trade unions. From 1909 to 1929, it functioned as a bastion for independent working class education.

Its origins lie in the 1909 strikes at Ruskin University, where many students had become dissatisfied with what was viewed as ‘pro-establishment’ control over the school curriculum. The striking students were supported by their own headmaster, Dennis Hird.

Several of these (now former) students would go on to form the Plebs’ League, centred around the teaching of Marxist principles. In 1909, on August 2nd, the League held a meeting at Oxford to pass a resolution calling for the establishment of the CLC to provide independent working-class education.

This College would be outside of the control of other universities, especially Oxford, and would be run by a committee made up of members from various socialist and Co-operative societies, as well as the Labour party itself. Dennis Hird, for his loyalty to the striking students, would become the new headmaster. The College would also receive its funding from two major trade unions: National Union of Railwaymen (NUR) and South Wales’ Miner’s Federation (SWMF).

And thus, was the Labour College born.

Its aims were to equip its students with the political and intellectual understanding and knowledgeto establish an efficient and cohesive outlook on organised movements and other socialist activities.

These were, in effect, the ‘social sciences’. The lectures and discussions revolving around these social sciences were given not just to the students, but to various members who hailed from unions supporting the college.

Another purpose of the College was to ensure a systematic organisation of the working class, whose goal was compatible with the economic conditions following World War I—critiquing on the ‘social hierarchies’ of society in accordance with the labour movement.

There were many different subjects taught at the Labour College (LC), including Co-operation, Economics, English Grammar, English Literature, Elocution, Evolution, Foreign Languages, History of Economic Theory, History of Political Institutions, History of the Modern Working-Class, Industrial History, Law and Morality, Municipal Government and Problems, and Sociology.

Initially, the College saw great success, moving to Earl’s Court London in 1911, and receiving official recognition in 1915 from the Trades Union Congress (TUC). In 1921, it was even declared as the centre of the National Council of Labour Colleges, a national network of other similar colleges.

The College was very selective in accepting students; it only accepted 12 between 1925-1927, among whom was Albert Knight. A few others include:

- Aneurin (Nye) Bevan, a Welsh Labour Party Politician, who studied Economics, Art and Politics at CLC, and would go on to become, as Minister for Health under Prime Minister Clement Atlee, the architect of the NHS.

- Frank Hodges, amongst the earliest students to the college and who would go on to become General Secretary of the Miner’s Federation of Great Britain (as well as an MP in 1923)

- Arthur J. Cook, a trade unionist who also became the General Secretary of the Miner’s Federation of Great Britain (and was especially prominent during the General Strike in 1926).

- William H. Mainwaring, a coal miner who became Vice-Principal of the CLC in 1919, (after attending in 1913), then rejoined the Labour party in 1924.

Unfortunately, some things were not made to last. In 1926, a proposal was made to merge the CLC and Ruskin College into a new Labour College based at Easton Lodge near Great Dunmow, Essex (known as the ‘Easton Lodge’ scheme).

However, a number of large trade unions opposed this scheme, seeing the manoeuvre as impractical in regards to funding (which, if the scheme went forward, would come from the unions themselves). A Card vote was held on 7 September to decide the matter; the Eastern Lodge scheme was rebuked by a large majority.

Three years later, the mining industry suffered severe losses during the Great Depression of 1929, placing funding for the College from the NUR and SWMF organisation in jeopardy.

In particular, the SWMF held a conference in Wales in April that year , deciding to discontinue funding if additional levies could not be raised from its members. This proved unsuccessful, as was the attempt to transfer control over the College to the wider trade union movement. By July, it had closed.

Had the Eastern Lodge scheme been successful and the merger happened, the Labour College may well have existed beyond 1929. As it stands, its winding up represents the closing of a vital chapter in the history of socialist movements within Britain.

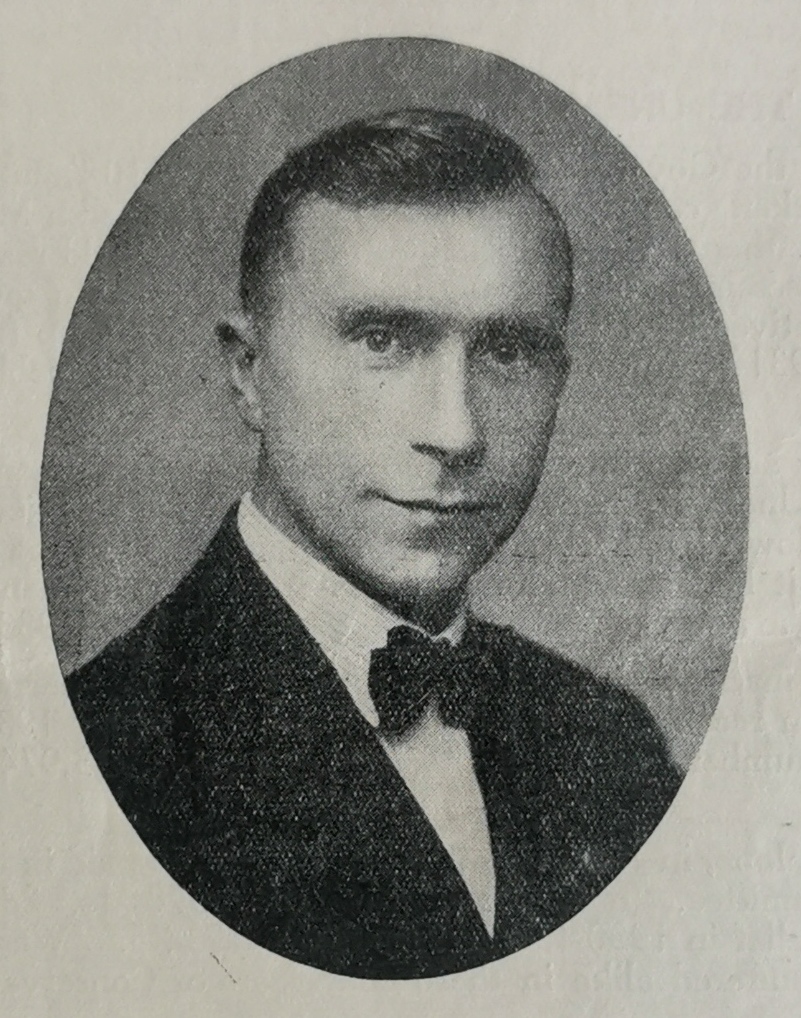

Who was Albert Knight?

Albert Knight was born in 1903 in the Forest of Dean. His father, Benjamin Knight, was a collier and later an engine driver on the Severn and Wye Railway. In 1910 the family moved to Lydney. A seven-year-old Albert was sent to the local council-run school, where he became enamoured with the school gardening and retained a great pleasure for gardening for the rest of his life.

From an early age, Albert was influenced by older members of several trade unions and socialists. He became a lad-porter for the Great Western Railway (GWR) at 14, and later – unsurprisingly – a contributions collector for the National Union of Railwaymen (NUR).

At the age of 18, he became secretary to the Lydney Trades and Labour Council and was later made an NUR delegate from the Lydney branch to the Bristol and South-West of England District Council. He further showed his dedication to socialism and working-class movements when he passed a Safe Working on Railways Certificate in 1922.

In 1925, he passed the examination set by NUR to enter the London Labour College, among 11 other students. Remaining at the CLC for two years, he spent much of his time there reading socialist works by Marx, Engels, Louis Boudin and Joseph Dietzgen. During this time in 1926, he also became a member of the Labour Party, kick-starting his long-running attempts to try and run for Parliament.

In August of that same year, Albert and six other LC students visited the Soviet Union. Travelling from London, their destinations included Lenin’s Mausoleum – which in 1926 was still in its original wooden construction – as well as the Karl Liebknecht Salt Mine in Bakhmut, named after the martyred German communist, and the historic Finland Station, where Lenin returned from exile in 1917.

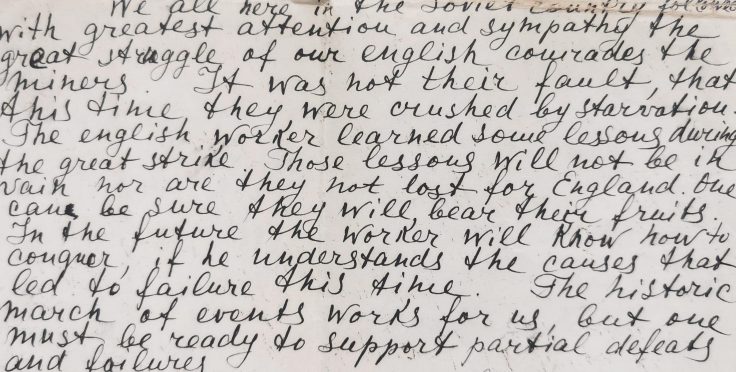

In the wake of their trip, their Soviet interpreter Alexandrov wrote to Albert Knight, sharing amongst other things his perspective on the 1926 general strike:

We all here in the Soviet country followed with greatest attention and sympathy the great struggle of our English comrades the miners. It was not their fault that this time they were crushed by starvation. The English worker learned some lessons during the great strike. These lessons will not be in vain… One can be sure they will bear their fruits. In the future the worker will know how to conquer, if he understands the causes that led to failure this time.

“A Letter from Leningrad”

Albert’s later years

As his term at the Labour College began to end, Knight sought other prospects in which he could serve the National CLC. Albert first returned to his old job as a porter for the GWR and later became a tutor and organiser for the NCLC in Manchester and Southeast Lancashire, between 1929-1936.

His most significant year came in 1936, when he not only joined the EC and the Publications Committee of the NCLC, but he also married Winnifred May, whom he had met when she was training as a teacher at the LCC in Furzedown.

Winnifred would go on to help Albert in his affairs at the NCLC with classes on women’s emancipation and the unemployed, even becoming a JP for the Chester Rural District in 1949. His classes were noted as highly significant, in that they doubled the number of attending students from 1935-1936; day school students went from 67 to 273 attendants, while occasional attendants rose from 3,120 to 4,534 (which was actually the inverse for the national average of attendance at schools at the time).

Knight’s time as the regional organiser saw him make annual reports on the productivity of Labour education, from 1930-1936, which serves as an excellent recording of the status of the NCLC at that time.

By October 1931, 60+ lectures were being given to co-operative guilds and labour unions and different branches of trade unions, all with full-time tutors. Knight spoke particularly passionately on the status of voluntary tutors as well, focusing on their necessity for education and the classes that his students should be taught:

The basic subjects of our teaching… form the starting point for the study of other subjects.

Albert Knight

Sadly, as volunteers for tutoring were not tied to the LC or to Knight specifically, they were often in short supply despite the great demand (as Knight noted in his annual report of December 1933).

Albert and Winnifred continued doing what they could despite the rapid decrease in the number of classes being taught, from 63 in 1926, to 54 in 1934 (as a result of under-funding by the NCLC). This included the teaching of ‘modern problems’ to students such as Clara Bamber, the future president of the Women’s Co-operative Women’s Guild.

Several of the lecturers who Knight invited included Sylvia Pankhurst (with a lecture on ‘The Struggle for Women’s Emancipation’) and the socialist economist Harold Laski. Albert remained a member of various TUC committees and several Whitley councils.

His kindness to others was apparent, as in 1934, when Albert and his wife helped shelter refugees, Irma and Peter Petroff, from Nazi Germany in their own home; he later gave lectures to the Ministry of Information while serving in Air Raid Precautions (ARP) during the second world war.

In 1936, he was offered the position of organiser for the northwestern area by the National Union of Public Employees (NUPE). He accepted (as he had grown fairly critical of J.P.M. Millar, the NCLC’s General Secretary), and eventually moved to Chester in 1938, becoming a full member of NUPE.

Knight remained the Treasurer of the Chester Trades Council from 1975-1978 (one year before his death), and was on the board of directors of the Chester Co-operative Council for more than twenty years. Likewise he remained a member of the Northwestern Labour Party’s regional council from 1955-1969.

He was also a member of the Chester and District Hospital Management Committee from 1948-1974, and remained with NUPE until his retirement in 1968, before being awarded an MBE in 1969. Last but not least, Knight helped fund a NCLC for deaf people, having almost gone deaf himself at forty years old but living without the assistance of hearing aids.

Albert Knight died on 16 December 1979 of heart failure, leaving behind a considerable legacy of hard work, determination and goodwill towards the national Labour movement as a whole.

His legacy remains enshrined here at BPHA, with photos of his trip to the Soviet Union, records of his run for parliament, and a bust of Karl Marx that had he had received as a gift from the French sculptor and grandson of Marx, Karl-Jean Longuet, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Marx’s death.

The duty of every individual in the movement is to put their weight on our side.

Albert Knight

Toby G., July 2023

Leave a comment